The night Barack Obama claimed victory in the Democratic presidential primaries in 2008, he predicted future generations would look back and say, “This was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.”

That turned out to be wrong. Earth kept getting hotter, the oceans kept rising, and Donald Trump spent four years undoing many of the clean energy policies adopted by his predecessor.

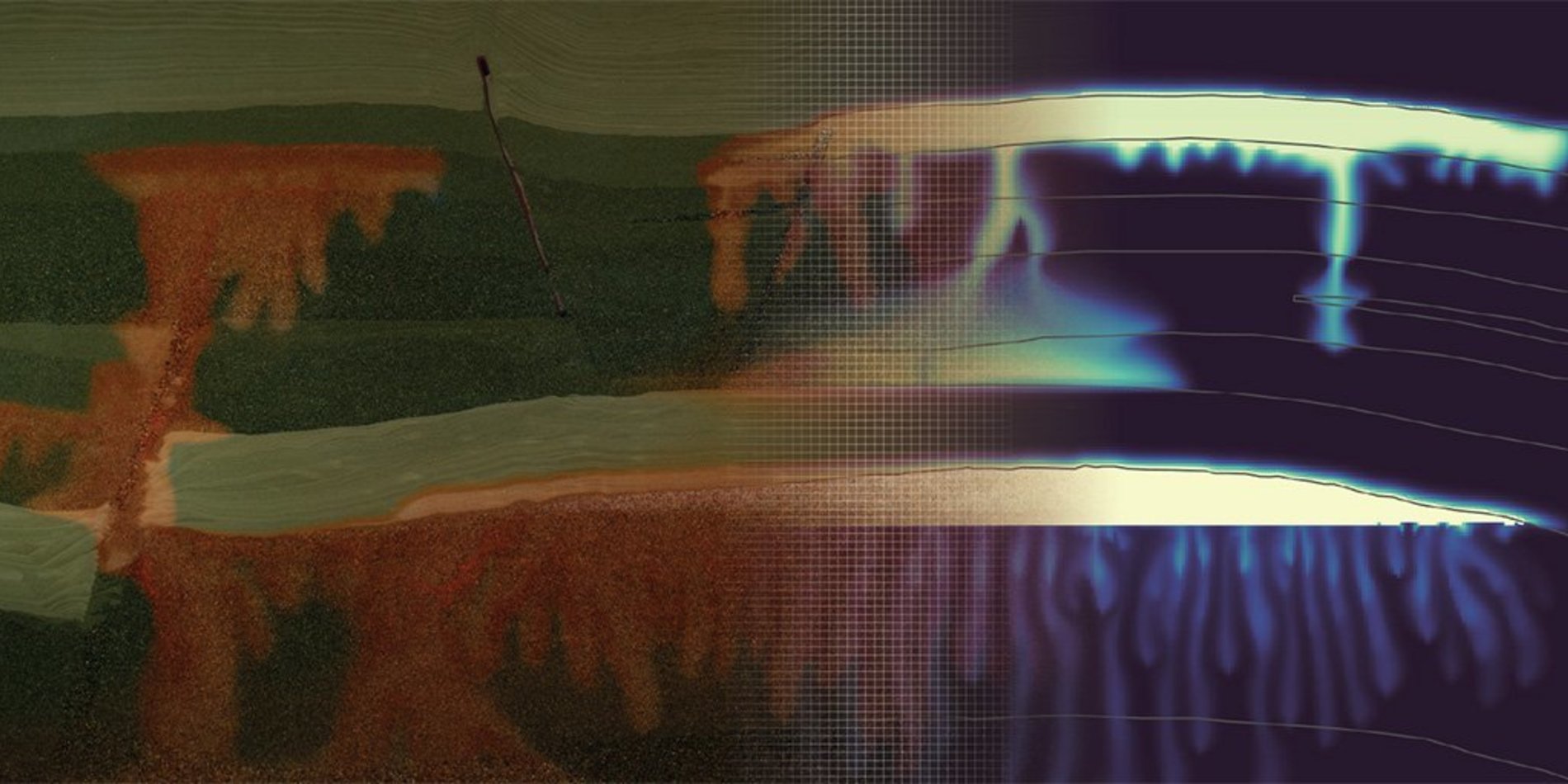

Tackling the climate crisis will once again take center stage under Joe Biden, but with an important shift. Although the energy politics of the last dozen years were defined by coal — with President Obama working to accelerate its decline and President Trump trying and failing to revive it — the fiercest battles of the Biden era are likely to revolve around another fossil fuel, natural gas.

The president-elect campaigned on 100% climate-friendly electricity by 2035, a timeline that could squeeze natural gas — currently the nation’s largest power source — off the power grid in the next 15 years. The short list of climate priorities on Biden’s transition website also includes “direct cash rebates and low-cost financing to upgrade and electrify home appliances,” which could mean replacing gas furnaces, water heaters and stoves with electric alternatives.

It’s an ambitious agenda that’s sure to expose fault lines in the Democratic Party, between renewable energy advocates who see natural gas as no better than coal and establishment figures who say the fuel still has a role to play in reducing pollution.

The battle is already underway, with rumors circulating that President Obama’s second-term Energy secretary, Ernest Moniz, is a top candidate to get his old job back under President Biden.

Moniz is a controversial figure among climate activists. He was a leading figure in Obama’s “all of the above” energy strategy, which celebrated U.S. oil production and envisioned gas as a “bridge fuel” to cleaner energy.

Moniz later joined the board of Atlanta-based Southern Co., whose power plants are among the most polluting of any major U.S. energy firm. He also founded the Energy Futures Initiative, a think tank whose advisory board is chaired by the former chief executive of British oil giant BP.

In September, 145 advocacy groups sent Biden a letter urging him to “ban all fossil fuel executives, lobbyists, and representatives from any advisory or official position” in his government. The signatories included 350.org, whose co-founder, Bill McKibben, described Moniz as “probably the one person environmentalists would least like to see involved in a Biden administration.”

“If Biden wins, it will be an early test of his seriousness,” McKibben wrote.

Two weeks before the election, Moniz offered a California-focused preview of the types of policies he might pursue.

In a report co-written with Stanford University researchers, Moniz’s Energy Futures Initiative argued that the Golden State would have a much easier time meeting its ambitious climate targets if it invested in technology to capture planet-warming emissions from power plants and industrial facilities before they could reach the atmosphere.

Known as “carbon capture and storage,” the technology faces economic challenges and has yet to make a serious dent in global emissions. But a handful of projects have started to come online. Centrist-minded climate advocates — and fossil fuel companies — see carbon capture as a way to combat global warming without having to totally eliminate coal, oil and natural gas.

The October report concluded that California could slash emissions by 60 million metric tons annually by 2030 — about one-third of the reduction the state hopes to achieve — by outfitting 76 industrial facilities and power plants with carbon capture systems.

In an interview, Moniz said the technology could help society increase its use of renewable energy. That’s because gas plants with carbon capture can provide climate-friendly electricity during times of day when the sun isn’t shining, the wind isn’t blowing and battery storage systems are tapped out.

“Frankly, it’s an enabler of introducing more renewables,” Moniz said.

But many progressives see continued reliance on natural gas as misguided, if not downright dangerous.

Part of their concern is that, even with carbon capture, gas plants would still spew local air contaminants such as nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds. Those pollutants would continue to affect public health in the low-income communities of color where electricity-generating stations and other polluting facilities are predominantly located.

“Carbon is not the only dangerous thing that comes out of cement and natural gas production by any stretch of the imagination,” said Mad Stano, senior legal counsel at the Oakland-based Greenlining Institute. “Reducing carbon alone is an insufficient climate policy, and it’s out of step with California’s emerging focus on recognizing climate equity and environmental justice.”

Even without those other pollutants, critics simply don’t trust that carbon capture technology will come through, especially after failures such as the Kemper coal plant in Mississippi, which received $270 million in federal subsidies and was championed by Moniz. Southern Co. canceled the project when it ran three years behind schedule and $4 billion over budget.

And if widespread carbon capture doesn’t pan out, activists worry that continuing to invest in gas plants and pipelines will lock in decades’ worth of carbon dioxide emissions. That could make it difficult to limit global temperature increases to 2 degrees Celsius or less, the goal adopted by nearly 200 nations in the Paris climate agreement, which Biden has pledged to rejoin.

Gas proponents point out that the fuel burns more cleanly than coal, and that power plant emissions have fallen since fracking made America the world’s leading gas producer, undercutting coal’s share of the electricity market.

“The majority of emissions reductions in the U.S. electric power sector have been from coal-to-gas switching, and that’s been true almost every year since 2005,” said Richard Meyer, managing director of energy analysis at the American Gas Assn. “For the next decade, we’re going to continue to see gas work creatively, flexibly, to continue to reduce emissions in the power sector.”

Some experts aren’t so sure. A recent study from researchers at UC Irvine and Global Energy Monitor found that replacing aging coal plants with new gas plants that could operate for 30 years or longer — as America has done in recent years — might reduce long-term carbon emissions by just 12%. The difference is even less after accounting for methane, a pollutant that leaks from gas infrastructure and traps heat in the atmosphere far more powerfully than carbon dioxide over the short term.

Scientists say humanity must achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. For carbon capture and storage, the key question may be which industries can phase out fossil fuels entirely and which won’t be able to avoid some continued emissions.

Hal Harvey, chief executive of the San Francisco-based research firm Energy Innovation, expects carbon capture to be most useful for cement plants and other industrial facilities — one of the main ideas outlined in the Energy Futures Initiative report.

But Harvey, who serves on the advisory board of Moniz’s initiative, thinks the technology will play a “niche role” on the power grid, at most. That’s because there are other ways to keep the lights on when solar panels, wind turbines and batteries aren’t enough.

Harvey listed geothermal and nuclear power, renewably produced hydrogen, better coordination between neighboring states and “demand response” programs that pay people to use energy at different times of day as a few of the possibilities.

He described carbon capture and storage as “an expensive approach and a limited approach.”

“If you took every oil well in the world, and every pipeline and every compressor and every oil ship, and ran them backward so that they stuffed [carbon dioxide] into the ground instead of pulling oil out, you would abate about 7% of annual emissions,” he said.

Moniz and his collaborators are more optimistic about carbon capture and storage.

The Energy Futures Initiative report acknowledges the technology is no “silver bullet.” But with a strong national carbon price that incentivizes companies to slash emissions, more carbon capture systems would be built, said Sally Benson, one of the report’s lead authors and co-director of Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy.

“Even though an individual project may not be economical,” she said, “from a society perspective it’s cheaper and more reliable.”

Moniz also defended his relationships with the fossil fuel industry. Although progressives tend to see oil and gas companies as an obstacle to be overcome — pointing to their long history of fighting climate action, and more recently their adoption of climate pledges that critics consider sorely lacking — Moniz sees the industry as a key partner.

“If we want to accelerate our decarbonization,” he said, “we better get these companies as part of the team.”

In contrast to the Green New Deal championed by climate activists, the Energy Futures Initiative proposed a “Green Real Deal.”

Both plans call for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and highlight the potential to create good-paying clean energy jobs. But Moniz’s proposal emphasizes technology flexibility and working with industry, while Green New Deal supporters envision faster and more sweeping change, including 100% clean energy by 2030 and a federal jobs guarantee.

However Biden chooses to move forward, he can look to California for guidance.

The state already gets more than half of its electricity from climate-friendly power sources, and Gov. Gavin Newsom recently instructed regulators to work toward ending the sale of gasoline-powered cars by 2035. Nearly 40 local governments have banned or limited gas hookups in new buildings, and state officials are studying how best to transition away from natural gas.

California also offers a preview of the challenges.

An August heat wave led to brief rolling blackouts, which officials blamed on poor planning but which critics worry will return if the state keeps shutting down gas plants. Southern California Gas Co., the nation’s largest gas utility, has fought local gas bans and warned that consumers won’t accept a future without gas stoves.

Elliot Mainzer will help determine whether the Golden State succeeds in leading the rest of the country toward 100% clean energy. He was recently hired to lead the California Independent System Operator, which manages the electric grid for most of the state. It’s a job that will only grow more important as cars, trucks and home heating systems hook up to the electric grid.

In a recent interview, Mainzer responded to a question about the costs of phasing out fossil fuels by emphasizing the costs of continuing to burn them: worsening wildfires, hotter heat waves, coastal inundation and mass species extinctions.

“We’re not decarbonizing the industry because it’s fun. We’re decarbonizing the industry because we’re trying to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. And the costs to society of not doing that are almost beyond imagination,” he said.

“We have to be willing to have the tough conversations about solutions,” he added. “We have to be able to call out concerns.”

Then, and only then, will the rise of the oceans begin to slow and the planet begin to heal.